Test Soda Firing #1 (8/11/20)

Lauren and I moved to Logan, Utah in July for me to start an MFA in Ceramics at Utah State University. My main goal here is to experiment with local materials; especially using local rocks to make glazes. I have been out to collect some samples, but before I dive into that research, I wanted to test the myriad of purchasable clays that the studio has for our use.

In pottery, clay is number 1. It is my main ingredient. The tomatoes in the tomato sauce. In North Carolina, I was making my own clay, a blend of four or five different local clays. But there isn’t a ton of local sources of clay in Utah. Plenty of rocks, but not much clay, really. Whilst I am here, I feel okay trying out these commercial clays and not going mad trying to harvest and process local clay, too. There are several rooms full of different kaolins and all sorts that I have access to. It’s a potters playground!

The system is very well set up at USU. As well as this marvelous array of materials, I also have access to a small bluebird mixer and a larger dough mixer for preparing clay. The larger mixer can do 200-300lbs in one go and the smaller one is more suited to 50-100lbs. Okay, so that’s the clay part… I want to test and see how they respond to soda firing.

WHY SODA?

As an apprentice and afterwards in North Carolina, I primarily fired my pots in wood kilns with the late addition of salt. The salt (NaCl) vaporises and sodium molecules bond with silica in the clay to produce a clear glaze on the pots. I love the surfaces that result from this atmosphere, but feel like I have a pretty good handle on it as a process.

Soda firing, however, is a whole other thing. The process is similar to firing with salt, but instead of sodium chloride, you introduce soda ash (Na₂CO₃) or baking soda (NaHCO₃). The sodium still reacts with the clay to form a clear glaze on the pots, but it is much less volatile. With salt firing you rarely get a dry surface; it flies so readily around the kiln reacting with the pots. With soda you get much more localized effects; each pot will have more soda on one side than the other. This makes for more dramatic surfaces.

Here’s what I mean. Below on the left is a salt glazed jar… the orange peel effect of the salt wraps around the whole pot in a pretty even way. The variation on the belly/shoulder of the pot is due to a light dusting of wood ash, not the salt. On the right is a soda glazed cannister jar out of my first soda firing. The area that got a lot of soda went grey and the area with less went red. There was a clay slip on each of these pots. You can see the darker clay color underneath the salt glazed jar and the lighter clay under the slip on the soda jar. This shows how much the clay is crucial in soda firing. The slip here is registering the level of soda far more than the white stoneware underneath would.

Salt glazed cannister jar, Hamish Jackson, fired in Lara O’Keefe’s salt kiln, 2019, NC.

Soda glazed cannister jar, Hamish Jackson, fired in the soda kiln at USU, 2020, UT.

I have wanted to delve into soda for a while now, but never had a real chance. This goal aligned with my other one of testing clays. I figured why not experiment with the available clays in the studio in the soda kiln. By doing so I would see how reactive they are and to try to understand their character.

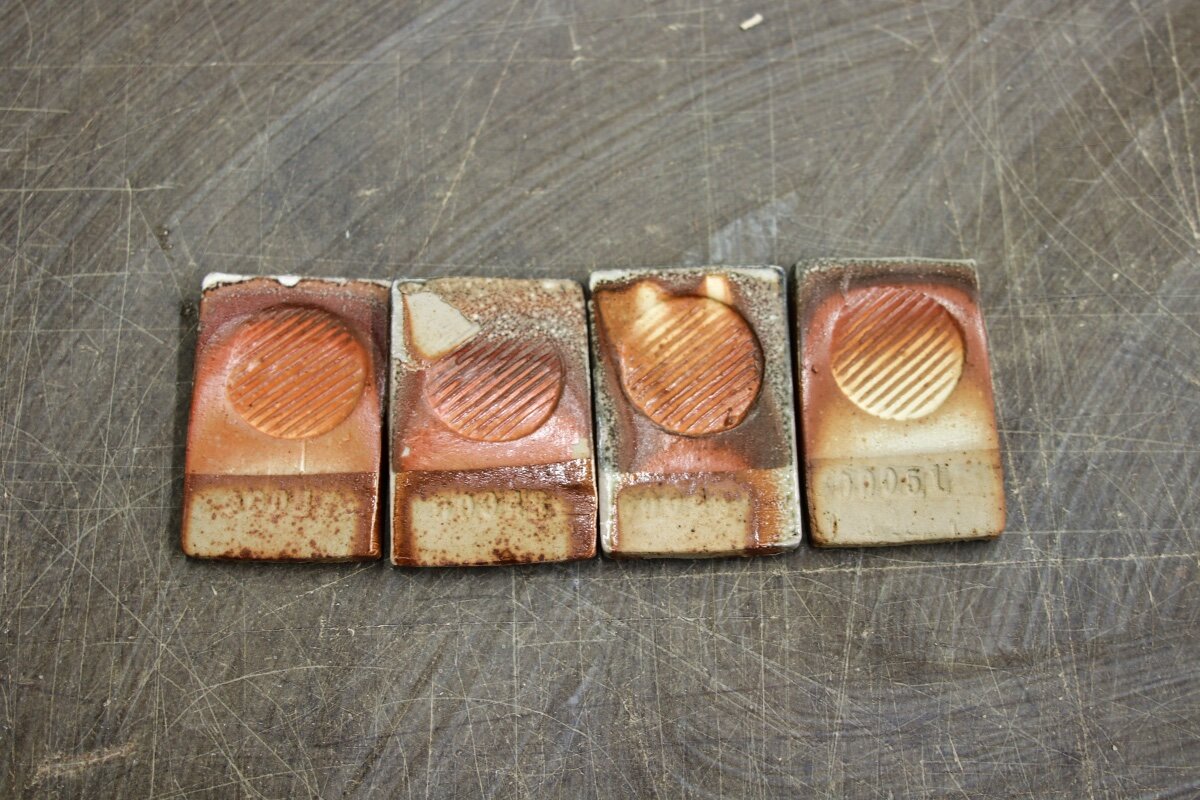

So for my first soda firing, I made a bunch of test tiles and some pots using a couple of clays recommended by Dan Murphy (one of the professors). I chose to run each slip test on 3 different clay bodies to see what difference that made. I used a high alumina porcelain, a white stoneware and an iron rich clay. Each test got 3 trials in the kiln. In retrospect, I wish I had made twice the amount of tiles so I could have saved a whole set for my next firing. But I got plenty of information anyway. It was an excellent exercise.

Before loading and firing, I spoke with several people about how they have approached soda: Casey Beck, Harry Levenstein, Louis Reilly, Denise O’Connell Joyal and Isaac Howard. It was super helpful to pick their brains before I got rolling. Check them out, they all make really lovely pots.

THE FIRING

I decided to fire in the way I thought would produce the best results (after much thought). I did an hour of body reduction when cone 010 went down, keeping the kiln in medium reduction on the way up and then sprayed in soda slowly over the course of 6 hours, starting when cone 7 went down, ending when cone 10 was down. I went in cycles, pushing the damper in when I introduced soda, with a couple of pieces of wood each time too, and then opened the damper back up to get the temp to rise back to where it had been. At the end of the firing, I let the kiln drop to 1850°F and then down-fired it in reduction to 1600°F. This was fairly time consuming and I was happy to have Tansy O’Bryant on the crew. She had pots in the kiln and was very helpful with the down-firing and clean up afterwards.

Alright, enough chatter. Here’s some of the results…

NOTE ON THE RESULTS

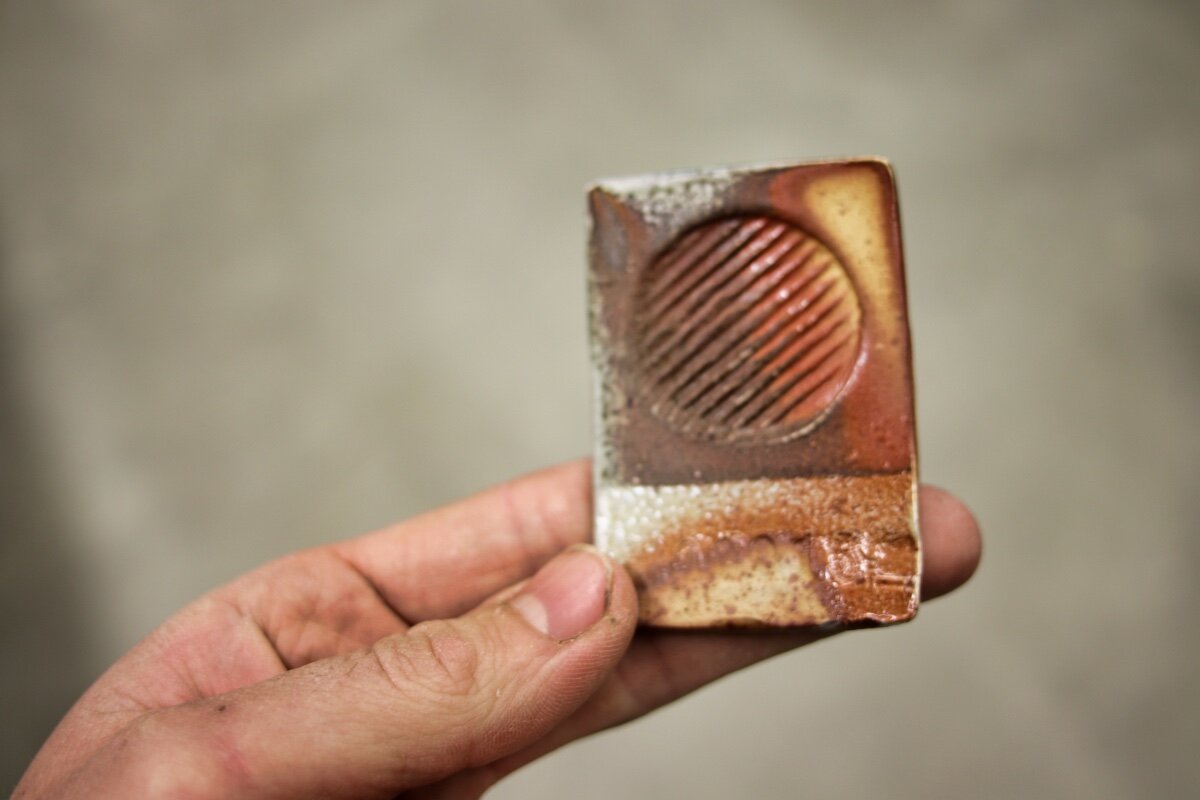

Some of the tests are based on a basic slip recipe (#6) with additions. #6 is 50% Helmar Kaolin : 50% OM4. Each test was dipped once to cover about 3/4 of the tile and then dipped again on the top 1/3. The tiles were packed in the kiln pretty tightly so often they only got dosed with soda on the edge/top corner. Most of the information about how the slip will act in soda is shown in these tight bands/gradients near the top of the tiles. I spent a lot of time staring at these tight lines of color to discern the results. Some of it is translatable in these pictures, but there is no substitute for handling the actual tiles. If only we had holographic technology!

Each set of test tiles fit on a single shelf (12” x 24”). To easily keep track, I put the white stoneware tests up top, the iron rich stoneware in the middle and the porcelain down low.

I recommend clicking one of the images to open a pop up window to view them.

The kiln was not entirely full of test tiles. Below are some pics of the kiln as I unloaded it…

Here are a few pictures of pots that were dipped in a couple of different slips. You get a much better feel for what the slips might do seeing them on a form rather than a test tile.

Finally, here’s the firing schedule and my initial notes from how it went (just in case I lose my notebook or someone burns it). I have summarized the notes below, so no need to zoom in and try and read my dodgy handwriting haha.

RESULTS/NOTES/CONCLUSIONS:

I will end with just some quick notes of the results:

Clay is of utmost importance. This was clearly shown by the test tiles. The iron rich clay was the most impacted by the reduction cooling (deep purples and reds). It was the least reactive/flashy, though. The porcelain flashed the brightest.

The white stoneware is definitely best for having slips applied over it. Many of them flaked off the porcelain and the stoneware is a white enough background to allow bright colorful slip action.

The porcelain on its own without a slip could be beautiful. Some of my favorite results were simply the plain porcelain clay ice cream and cereal bowls…

Brighter color where less soda: Heavy soda tends towards light or dark grey.

Neph sye brightens colors and flashes well. As you increase the quantity of it in a slip it fluxes it more and the flashing lines get more blurry'/less defined (above 35%).

Talc might be an interesting addition to a clay body: For color response and resist the soda.

PACK THE KILN BETTER! Try to use less shelves and stagger the pots on each shelf to allow soda to travel around more easily.

Placing pots very close together produced flashing, but you have to let the flame and soda get there.

Not sure how much of an effect the reduction cool had. Also not sure how much the wet wood that I introduced (water) affected the results.

Used 10lbs soda, all sprayed in to the fireboxes. The middle of the kiln was pretty dry, the top and bottom got a good bit of soda.

* * *

Thanks for reading. Especially if you got all the way this far reading it all! Happy Holidays to you and yours! I’ll be posting about my #2 SODA FIRING in the next day or so.