Becoming a Beekeeper: My first year keeping bees in North Carolina.

I've been interested in beekeeping for some time, but never had the impetus to start until I became friends with some local beekeepers when we moved to Chatham County. I joined the Chatham County Bee Association and started going to their 'Field Days' at the Community College in Pittsboro. The association manages an apiary there for teaching purposes. I had never seen a hive worked before and it immediately made me want to get into it. Seeing the frames of bees and honey being removed from the hive and inspected was magic. Going to association's monthly meetings showed me that there was a whole world to learn about bees and beekeeping.

Local beekeepers told me to take "Bee School," a bi-annual class run nearby in Pittsboro, before getting my own hives. I was absolutely going to take this advice, but an opportunity presented itself in the fall when a chap in the association wanted to get rid of his hives. He had started them the previous spring and they were doing well, but his niece and nephew had been stung a few times. So I took the opportunity and got them.

I'll describe my first year beekeeping by the season, as it is a highly seasonal pursuit.

AUTUMN

I got the hives on September 11th 2016. They had been started off from packages in the spring of 2016. They had grown up to fill out two deep boxes and one medium each.

My master/mentor Mark and his wife Carol kindly let me put the hives on their property, down in in the apple orchard behind the pottery. I weed-whacked around the area and put down a tarp to help prevent weeds taking over and set up breeze blocks on flat spots for the hives. I wanted to expand the apiary to four hives, so I leveled and set up those spots in advance. It's nice having the hives at work as I can go and check on them at lunchtime.

A couple of friends who are beekeepers helped me move them and advised me on preparing for overwintering. In our area, it's common to have to feed the bees diluted honey water or sugar water in Autumn to make sure they have the food stores to get through winter. I didn't have to feed them much, though, as they had decent enough stores already. Moving them wasn't too bad--we did it at night, with a wire mesh stapled to the front entrance of the hives to stop any bees escaping. We tied a ratchet strap tightly around each and used a hive lifter (which clamps under the handles) to get them onto the bed of the pick up truck. The journey was only about five miles, but I was still worried all the way there!

We arrived safely and placed them down carefully, leaving the hive closed for a couple of days. Once opened up, the bees reoriented themselves by flying in circles around the hive. It was pretty cool to see, but I made sure to give them some space and not disturb them for a couple of weeks, just observing from a distance.

I named the hive on the left Rosemary and the one on the right Thyme. Bees actually hate thyme oil so this was a poor choice in retrospect. I din not know this at the time. Rosemary has always been a step ahead of Thyme.

My first major mistake was being convinced that Rosemary did not have a Queen. I could not see any sign if her, nor eggs or larvae. So I found another Queen and introduced her to the hive. I introduced her slowly as you are supposed to... putting her in a cage watched inside the hive for 3 days. When 3 days were up I let her out, only to see her balled up by workers. They stung her till she was no more. It was a sad moment. The workers are very sensitive to a new Queen with different pheromones, and will only accept her if they really are Queenless. The Queen slows down laying at the end of Autumn and stops altogether in winter so this is what must have occurred: I didn't see any fresh eggs because she wasn't laying.

In early October 2016, we had a scare from Hurricane Matthew, so I prepared the hives as shown below. Thankfully the main part of the storm missed us, and the hives were fine.

WINTER

Once the weather got cold, I pretty much left the hives alone. You don't want to open them up and let warmth out during the winter. On the occasional warm day, I had a peek in to see how the stores were holding up. It was a pretty mild winter by all accounts, apart from a couple of brutal weeks, and they came through fine, with no additional feeding. Come January/February, I gave them a little pollen and sugar to get them excited for spring.

"Bee School" ran in the winter--one evening every week from eight weeks--and taught me a lot about bees. In particular, I learnt about bee biology and how their colony functions. Bees are complicated creatures! It was an excellent course and I thoroughly recommend taking a similar course if it is available in your area--but there is a big difference between the theory of beekeeping and the actuality of working a hive.

One of the best parts of bee school was the equipment building week.

Going out to the field days and watching inspections in action taught me more of the physical and practical skills. It's ideal to find a mentor to show you the ropes if possible; I've been fortunate enough to have several people to discuss problems with and to come and help out.

SPRING

Once the weather warmed up some (Febuary/March), the bees started going out and foraging again, and the Queens started laying eggs again.

Both of my hives built up pretty fast--in part I think because of the pollen I gave them (not sure I will do this again). By the time I did a full inspection with a beekeeping friend, the hives had already both swarmed.

I was slow on the uptake and totally missed the signs (Queen cells) and a cramped hive. So in early Spring I had two hives with zero Queens. Bad news. But I did have four Queen cells in one hive, and five in the other. These are larger cells which the workers feed extra Royal Jelly (bee superfood) and then the egg develops into a Queen. If you have more than one emerge at the same time, they will fight to the death! If one emerges before the others then she will go and sting all the other Queen cells before they can. There can only be one Queen in any house!

With the help of Gerald Wert--an experienced local beekeeper--we split these two hives into five, each with one or two Queen cells. I would have never taken such a dramatic course of action, but now see it was the right course of action. I only wanted four hives, but Gerald advised to make more just in case. The hope was that each of them would make a new Queen, but sadly two of them didn't take. This is not uncommon. So I combined two of the hives (one Queenless with one Queen right) and managed to procure a VSH Queen (see below) from a local supplier to put into one of them. So at the end of spring, I had four laying Queens in four hives. They were weak but Spring is the time of year when there is plenty of forage out there for the bees.

Marjoram and Basil had joined the apiary!

SUMMER

Early summer is typically when beekeepers extract honey in my area. I was all excited and ready to try in June, managed to borrow a centrifugal extractor, and had all my equipment set and ready. Unfortunately, upon full inspection it was clear that the hives didn't have enough stores for extraction. I was not hoping to take much, the hives being young and all, but it was still a tad disappointing. I could have taken a few frames from Rosemary, who was the heaviest by far, but the Queen had been up in the honey supers, laying eggs on the back of frames of honey... this meant that if I extracted that honey then those babies would be lost. I wasn't about to do that! There was literally only one viable frame, which I took and scraped out. It was enough to fill one small glass jar. It tastes good though: we've been enjoying it for breakfast (sparingly) on sourdough toast.

I did a "sugar shake" to see how many varroa mites were in each hive. Varroa mites are the worst pest affecting bees worldwide (except possibly humans). They only made their way to North Carolina in 1990 but have been wreaking havoc since. Last year, 40% of all bee hives were lost in our state, and this is at least in part due to varroa mites. They spread viruses and diseases and can weaken the colony significantly.

There are guidelines for how many mites is acceptable in a hive, laid out by the state inspectors and general literature. Nine mites per 300 bees is the maximum that is acceptable. Rosemary came in at three, Thyme at 18, Basil at 10, and Marjoram at zero. There are two main ways of dealing with the mites: treating the hive, as you would if you got head lice--with a chemical that kills them--or re-queening the hive. I decided to use Api-Guard, which is a product, somewhat ironically, made from thyme. It is a soft-chemical, but a chemical nonetheless, and I felt bad about inflicting it on the bees. It is not easy trying to kill a small bug on a larger bug. Next time I think I will try re-queening with VSH Queens... these are Queens who have been bred to be "hygienic:" their offspring tend to clean themselves super well, and dump the varroa mites off them.

The treatment worked well enough--I had a significant drop in varroa mites in those hives, and the Queens got back to laying again.

AUTUMN 2017

It was just about a year ago that I got Rosemary and Thyme. I have made many mistakes not to be repeated, and am currently just giving the hives a little sugar water to make sure they have enough food to get through the winter!

FURTHER MISTAKES:

It took me awhile to get over the sense of fear when pulling apart the home of 30,000 bees (I haven't counted, but that's a conservative estimate). To begin with, I got stung quite a bit: partly this was because I was clumsy... dropping a whole frame of bees usually means you are going to get stung! Also, going down to the apiary without a lit smoker is silly--even if you try not to use it, its nice to have if the bees get riled at all. It blocks their pheromones and tends to make them more docile.

Going barefoot is a bad idea when inspecting, and shorts can also be problematic. Trousers with elastic bands around your ankles are really nice so the bees don't crawl up your legs. I don't practice this, but can see how it would be nice! A veil is essential when you are starting out--the bees tend to fly at your face and eyes when defending the hive. Having not tied my veil up properly and been stung on the eyebrow once, I know the value of the veil. Gloves tend to hinder me more than help, though.

One time I got stung quite a few times in one place on the thigh (wearing shorts), and came out in hives all over my body. Had to nip down to emergency care for a shot of steroids in the buttocks. Apparently this can happen if you get stung right in a vein. I have only had this reaction once. Fingers crossed it doesn't happen again. I now have an EPI pen in my beekeeping stuff too.

OTHER BASIC INFO:

Life cycle of the honey bee:

Worker bee service:

1-2 days: Cleaning cells and warming the brood nest, eat pollen and beg for nectar by older bees passing by.

3-5 days: Some of earlier tasks plus feeding older larvae with honey and pollen.

5-8 days: Nurse bees-hypoparyngeal gland is well developed so they can produce royal jelly to feed young larvae and Queen bee.

8-12 days: Take/process incoming food; ripen honey/store pollen.

12-16 days: Wax glands well developed; produces wax and constructs comb, ripens honey.

17-21 days: Guards hive entrance and ventilates hive, orientation flights.

22 days +: Forage for nectar, pollen, propolis and water.

Helpful Resources:

The CCBA (Chatham County Bee Association) has been amazing; I would have struggled much more had it not been for them. Each meeting has a different speaker come and present on a specific topic such as "using honey as medicine" or "tackling varroa mites." Whilst some of this goes over my head, I always learn things.Wherever you are, join the club--beekeepers who will more than likely want to help you with your bees.

In North Carolina, we have an amazing resource at our disposal--the state-supported (and funded) Apiary Services Program. NC is divided into six zones, each with its own inspector. You can call them out to check on your bees. Ours is Don Hopkins: he is extremely knowledgeable, and taught the bee school section on diseases, pests, and pest management.

There are a lot of books on beekeeping out there, but these are a few I have enjoyed and found useful:

First Lessons in Beekeeping by Keith S. Delaplane

Beekeeping for Dummies by Howland Blackiston

The Beekeeping Bible by Richard A. Jones and Sharon Sweeney-Lynch

I recently took a test to be basic "Certified" beekeeper but it goes up to Journeyman, Master and Master Craftsman. Heres the site: www.ncbeekeepers.org/master-beekeeper-program

Some beauty to end on:

|

| Honey and bees! |

Local beekeepers told me to take "Bee School," a bi-annual class run nearby in Pittsboro, before getting my own hives. I was absolutely going to take this advice, but an opportunity presented itself in the fall when a chap in the association wanted to get rid of his hives. He had started them the previous spring and they were doing well, but his niece and nephew had been stung a few times. So I took the opportunity and got them.

I'll describe my first year beekeeping by the season, as it is a highly seasonal pursuit.

AUTUMN

I got the hives on September 11th 2016. They had been started off from packages in the spring of 2016. They had grown up to fill out two deep boxes and one medium each.

My master/mentor Mark and his wife Carol kindly let me put the hives on their property, down in in the apple orchard behind the pottery. I weed-whacked around the area and put down a tarp to help prevent weeds taking over and set up breeze blocks on flat spots for the hives. I wanted to expand the apiary to four hives, so I leveled and set up those spots in advance. It's nice having the hives at work as I can go and check on them at lunchtime.

A couple of friends who are beekeepers helped me move them and advised me on preparing for overwintering. In our area, it's common to have to feed the bees diluted honey water or sugar water in Autumn to make sure they have the food stores to get through winter. I didn't have to feed them much, though, as they had decent enough stores already. Moving them wasn't too bad--we did it at night, with a wire mesh stapled to the front entrance of the hives to stop any bees escaping. We tied a ratchet strap tightly around each and used a hive lifter (which clamps under the handles) to get them onto the bed of the pick up truck. The journey was only about five miles, but I was still worried all the way there!

|

The hives in their new spot.

|

We arrived safely and placed them down carefully, leaving the hive closed for a couple of days. Once opened up, the bees reoriented themselves by flying in circles around the hive. It was pretty cool to see, but I made sure to give them some space and not disturb them for a couple of weeks, just observing from a distance.

I named the hive on the left Rosemary and the one on the right Thyme. Bees actually hate thyme oil so this was a poor choice in retrospect. I din not know this at the time. Rosemary has always been a step ahead of Thyme.

|

| Rosemary, in the back of the photo, building up like crazy--lots of foraging and new bees, whereas Thyme in the front is not doing so well. |

My first major mistake was being convinced that Rosemary did not have a Queen. I could not see any sign if her, nor eggs or larvae. So I found another Queen and introduced her to the hive. I introduced her slowly as you are supposed to... putting her in a cage watched inside the hive for 3 days. When 3 days were up I let her out, only to see her balled up by workers. They stung her till she was no more. It was a sad moment. The workers are very sensitive to a new Queen with different pheromones, and will only accept her if they really are Queenless. The Queen slows down laying at the end of Autumn and stops altogether in winter so this is what must have occurred: I didn't see any fresh eggs because she wasn't laying.

|

| Experienced beekeeper Lori Hawkins on the right describing how to pick up a frame properly. |

In early October 2016, we had a scare from Hurricane Matthew, so I prepared the hives as shown below. Thankfully the main part of the storm missed us, and the hives were fine.

|

| Hurricane prep. |

Once the weather got cold, I pretty much left the hives alone. You don't want to open them up and let warmth out during the winter. On the occasional warm day, I had a peek in to see how the stores were holding up. It was a pretty mild winter by all accounts, apart from a couple of brutal weeks, and they came through fine, with no additional feeding. Come January/February, I gave them a little pollen and sugar to get them excited for spring.

|

| Me and some of my ladies. |

|

| Bee School secrets inside. |

|

| This is an empty frame, waiting for the wax foundation to be inserted into it. This thin layer helps get the bees started building comb. They will do it on their own but it helps speed things up. |

|

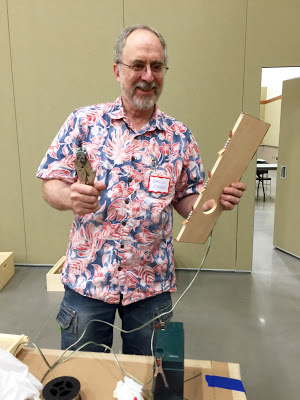

| This is David Jones, demonstrating his homemade device for embedding the wax foundation onto the wire supports by sending a quick blast of electricity through them which melts the wax just enough. |

|

| My hive tool resting on the box. The scraping side is helpful to remove sticky propolis, which the bees use to glue the hive together. The hooked side helps lift frames out of the box. |

SPRING

Once the weather warmed up some (Febuary/March), the bees started going out and foraging again, and the Queens started laying eggs again.

|

| You can see some tiny tiny freshly laid eggs in this picture--they look kind of like rice. Unfortunately the Queen laid them in between the boxes in "burr comb" which broke as I opened the hive up. |

|

| Spot the DRONE. There is only one here. |

I was slow on the uptake and totally missed the signs (Queen cells) and a cramped hive. So in early Spring I had two hives with zero Queens. Bad news. But I did have four Queen cells in one hive, and five in the other. These are larger cells which the workers feed extra Royal Jelly (bee superfood) and then the egg develops into a Queen. If you have more than one emerge at the same time, they will fight to the death! If one emerges before the others then she will go and sting all the other Queen cells before they can. There can only be one Queen in any house!

|

| You can see worker larvae developing in these cells. The bee with its head in there is a nurse bee feeding the young larvae. |

With the help of Gerald Wert--an experienced local beekeeper--we split these two hives into five, each with one or two Queen cells. I would have never taken such a dramatic course of action, but now see it was the right course of action. I only wanted four hives, but Gerald advised to make more just in case. The hope was that each of them would make a new Queen, but sadly two of them didn't take. This is not uncommon. So I combined two of the hives (one Queenless with one Queen right) and managed to procure a VSH Queen (see below) from a local supplier to put into one of them. So at the end of spring, I had four laying Queens in four hives. They were weak but Spring is the time of year when there is plenty of forage out there for the bees.

Marjoram and Basil had joined the apiary!

SUMMER

Early summer is typically when beekeepers extract honey in my area. I was all excited and ready to try in June, managed to borrow a centrifugal extractor, and had all my equipment set and ready. Unfortunately, upon full inspection it was clear that the hives didn't have enough stores for extraction. I was not hoping to take much, the hives being young and all, but it was still a tad disappointing. I could have taken a few frames from Rosemary, who was the heaviest by far, but the Queen had been up in the honey supers, laying eggs on the back of frames of honey... this meant that if I extracted that honey then those babies would be lost. I wasn't about to do that! There was literally only one viable frame, which I took and scraped out. It was enough to fill one small glass jar. It tastes good though: we've been enjoying it for breakfast (sparingly) on sourdough toast.

|

| A frame from one of Lori's hives: it is full of capped honey and ready for extraction! |

I did a "sugar shake" to see how many varroa mites were in each hive. Varroa mites are the worst pest affecting bees worldwide (except possibly humans). They only made their way to North Carolina in 1990 but have been wreaking havoc since. Last year, 40% of all bee hives were lost in our state, and this is at least in part due to varroa mites. They spread viruses and diseases and can weaken the colony significantly.

|

| One frame removed. |

There are guidelines for how many mites is acceptable in a hive, laid out by the state inspectors and general literature. Nine mites per 300 bees is the maximum that is acceptable. Rosemary came in at three, Thyme at 18, Basil at 10, and Marjoram at zero. There are two main ways of dealing with the mites: treating the hive, as you would if you got head lice--with a chemical that kills them--or re-queening the hive. I decided to use Api-Guard, which is a product, somewhat ironically, made from thyme. It is a soft-chemical, but a chemical nonetheless, and I felt bad about inflicting it on the bees. It is not easy trying to kill a small bug on a larger bug. Next time I think I will try re-queening with VSH Queens... these are Queens who have been bred to be "hygienic:" their offspring tend to clean themselves super well, and dump the varroa mites off them.

The treatment worked well enough--I had a significant drop in varroa mites in those hives, and the Queens got back to laying again.

AUTUMN 2017

It was just about a year ago that I got Rosemary and Thyme. I have made many mistakes not to be repeated, and am currently just giving the hives a little sugar water to make sure they have enough food to get through the winter!

|

| Some extra equipment I managed to get at a good price through the CCBA, ready for next year. |

FURTHER MISTAKES:

It took me awhile to get over the sense of fear when pulling apart the home of 30,000 bees (I haven't counted, but that's a conservative estimate). To begin with, I got stung quite a bit: partly this was because I was clumsy... dropping a whole frame of bees usually means you are going to get stung! Also, going down to the apiary without a lit smoker is silly--even if you try not to use it, its nice to have if the bees get riled at all. It blocks their pheromones and tends to make them more docile.

Going barefoot is a bad idea when inspecting, and shorts can also be problematic. Trousers with elastic bands around your ankles are really nice so the bees don't crawl up your legs. I don't practice this, but can see how it would be nice! A veil is essential when you are starting out--the bees tend to fly at your face and eyes when defending the hive. Having not tied my veil up properly and been stung on the eyebrow once, I know the value of the veil. Gloves tend to hinder me more than help, though.

One time I got stung quite a few times in one place on the thigh (wearing shorts), and came out in hives all over my body. Had to nip down to emergency care for a shot of steroids in the buttocks. Apparently this can happen if you get stung right in a vein. I have only had this reaction once. Fingers crossed it doesn't happen again. I now have an EPI pen in my beekeeping stuff too.

OTHER BASIC INFO:

Life cycle of the honey bee:

|

Type

|

Egg

|

Larva

|

Cell capped

|

Pupa

|

Average Developmental Period

|

Start of Fertility

|

||||||||

|

Queen

|

3 days

|

5 1/2 days

|

7 1/2 days

|

8 days

|

16 days

|

Approx. 23 days

|

||||||||

|

Worker

|

3 days

|

6 days

|

9 days

|

12 days

|

21 days (Range: 18-22days)

|

N/A

|

||||||||

|

Drone

|

3 days

|

6 1/2 days

|

10 days

|

14 1/2 days

|

24 days

|

Approx. 38 days

|

Worker bee service:

1-2 days: Cleaning cells and warming the brood nest, eat pollen and beg for nectar by older bees passing by.

3-5 days: Some of earlier tasks plus feeding older larvae with honey and pollen.

5-8 days: Nurse bees-hypoparyngeal gland is well developed so they can produce royal jelly to feed young larvae and Queen bee.

8-12 days: Take/process incoming food; ripen honey/store pollen.

12-16 days: Wax glands well developed; produces wax and constructs comb, ripens honey.

17-21 days: Guards hive entrance and ventilates hive, orientation flights.

22 days +: Forage for nectar, pollen, propolis and water.

Helpful Resources:

The CCBA (Chatham County Bee Association) has been amazing; I would have struggled much more had it not been for them. Each meeting has a different speaker come and present on a specific topic such as "using honey as medicine" or "tackling varroa mites." Whilst some of this goes over my head, I always learn things.Wherever you are, join the club--beekeepers who will more than likely want to help you with your bees.

In North Carolina, we have an amazing resource at our disposal--the state-supported (and funded) Apiary Services Program. NC is divided into six zones, each with its own inspector. You can call them out to check on your bees. Ours is Don Hopkins: he is extremely knowledgeable, and taught the bee school section on diseases, pests, and pest management.

There are a lot of books on beekeeping out there, but these are a few I have enjoyed and found useful:

First Lessons in Beekeeping by Keith S. Delaplane

Beekeeping for Dummies by Howland Blackiston

The Beekeeping Bible by Richard A. Jones and Sharon Sweeney-Lynch

I recently took a test to be basic "Certified" beekeeper but it goes up to Journeyman, Master and Master Craftsman. Heres the site: www.ncbeekeepers.org/master-beekeeper-program

Some beauty to end on:

|

| Here's a picture of some native bees on a cacti flower, atop a cliff, on the island of St John in the Virgin Islands last Spring. |